(The acme of music)

[In] sound itself, there is a readiness to be ordered by the spirit and this is seen at its most sublime in music—Max Picard

Away from Metaphysical Antirealism, views of some logical positivists and some die-hard scientists there exists a receptive, tolerant seminary somewhere in the east of the heart of India. One will be disheartened to find no priests, ministers or rabbi here. Only a void of eternal, enduring permanence continues to prevail in absence of one disciplinarian scholar. If one has the inclination for listening to voids, I would submit ‘look no further’. But beware this bears no similarity to hearing cosmic voids in modern physics with tools and devices borne by the contemporary man.

The look of this emptiness in Maihar is deceptive. An elementary two storied green and red receptacle of brick and mortar at one time would temperately invite serious enthusiast of music to drown in the world of nodes and anti-nodes of waves, they have hitherto unheard of. And this was free, attracting no charges. The business was genuine, honest, thoughtful and bore no nonsensical exercise. Which attribute would one choose for this lean, soft spoken, inconspicuous bald-headed man who cared little for himself and would often turn a harsh, strict disciplinarian to teach his students a lesson? He was not a man easily recognisable in the crowd but his endurance, tireless energy and resilience brought him to the helm of Indian classical music as one of the finest teachers the world has ever produced. Ravi Shankar, Khan’s son Ali Akbar, Nikhil Banerjee, Allauddin’s daughter Annapurna and noted flautist Pannalal Ghosh from Calcutta will all affirm in silence. Some serious questions still await answers to be delivered about this Muslim boy of ten who played truant, broke himself away from the restraints of a school, stole money and left his home (now in present day Bangladesh) without notice, hooked up with the sadhus in Calcutta, joined a Hindu family and received love and affection and turned an authoritarian enforcer of rules and regulations in serious schooling in music.

Acharya Allauddin Khan, the noted sarod player’s home at Maihar in the state of Madhya Pradesh in India will hold no secret when a visitor decorously bows in reverence in penultimate silence to listen to the voice of his instruments dispersing from its silent walls. An accomplished, multifaceted protean who could effortlessly play innumerable implements was himself a man of silence, who boasted little about himself. And he was a courageous God loving man and not a God fearing one, not attentive to the verbosity of the common people, what they said about him and what they said not. Possibly this was one of the reasons he could readily decorate the walls of his residence with Gods and Goddesses from all religions and this routine is still being followed through his generations.

William Shakespeare long back in 1601 had hinted about the metaphysics of music in ‘Twelfth Night’ when the bard spoke. Music is expressive and profound unlike written words in literature and assembles a compelling weighty environment in the mind of an empathising listener. Its fluidity and dynamics can elevate or transcend its hearer to another level of existence. This surely is not “Speculative Metaphysics” intentionally incorporated by the so called ‘Magic Healers’. On entering the world of Maestro Allauddin Khan’s spartan existence, now called his home at Maihar a sense of gratitude and gratefulness quietly descends and encompasses a melophile who unknowingly has turned a melomaniac with time going past. What can be more precise and pliable at one go? Here Khan’s protoplasm, soul and passion has turned into one permanence. This unicameral existence respects pre seventeenth century metaphysics no doubt but flouts and defies modern metaphysics, that nothing in this world is permanent.

A stubborn wooden bed that easily should be called a bunk, embellished with nothing but uncompliant firmness and rigidity eats up most part of a small room on the left of the drawing room for the guests. Here in Khan’s bedroom open space is scarce but the walls adorned with photographs of great men like Tagore and Swami Vivekananda, with others turned dark with passage of time, ensures Khan’s respects for those who influenced the world. A modern enthusiast of music will not be attracted to the repulsiveness of this cubicle. It is too dark and inelegant to be called a resting place for a tiring soul. But it mattered little to Khan, a restless, inconstant man fidgeting for harmony in sound.

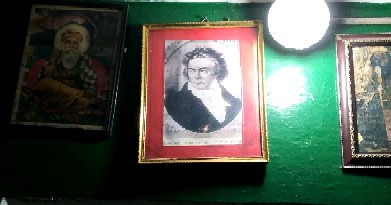

Another small room on the right cramped yet neat, exhibits the musical instruments encased in glass, Khan had used in his lifetime. A gramophone rests at the corner of the room where Khan might have enjoyed Beethoven. This room is a fitting, quintessential representation of Khan’s multifaceted, adroitness. An utter surprise awaits when one raises his eyes for the cornice. A photograph of Beethoven adorns and stares at Allaudin when he takes a break. It is rare for a music lover to find a western classicalist in a home for an eastern virtuoso. This echoes how tolerant and accepting Khan was. Only a truly, liberated educated man has the ability to recognise another man’s scholarship. A gleaming ray of radiance emerging from an open courtyard will attract anyone to the sunlit atrium bordered by a sprawling verandah of repute where Khan disbursed his wisdom, as free as fluid without hindrance. Rare movie albums depict Khan, sitting on a hard, unelaborated wooden chowki teaching his students no other than Ravishankar, Ali Akbar and Nikhil Bandopadhyay in those days.

After one exits Khan’s elementary home, the brightly coloured off-white, lilac, catenary arched mausoleum on the right attracts. The arch on this one storey construction reflects serenity found in Tagore’s Shantiniketan. Here rests two ever-indissoluble souls, ground down, that of Khan’s and his wife, now turned dust after time has elapsed silently.

After I had paid my respect to Khan’s grave I sat on its stairs, but not to dawdle away my time, only to find another middle-aged visitor taking a short nap.

‘Visited the place?’ I asked him, showing the red-green house behind me. He nodded in yes.

‘It’s a spellbinding place, I must admit’ I continued, ‘Are you a musician?’ I asked.

‘Me? You make me laugh, Babuji (Sir). I can neither read nor write.’ I noticed his boring lungi and the hackneyed waist-coat I had missed. He must be a local man I wondered. ‘But I listen to music. It comforts me so much that I can’t stop listening to it,’ he persisted, ‘I care

little what the music is, but there must be a melody to touch everyone’s heart.’ He didn’t stop here and kept talking to himself.

‘The music these days has lost its harmony. Believe me the melody is nearly lost’ and he stopped here I believed.

It was time for me to leave and I turned to get into my shoes.

‘Where’s the other man gone?’ I asked the chowkidar pointing at the extreme end of the staircase.

‘Who?’ casually replied the watchman, ‘You are the only one sitting here, I have already locked the gates. Its already five and the museum is closed.’

I no more could find the odd local man I had met.

(Photographs by author with verbal permission from caretaker of Madina Bhavan)